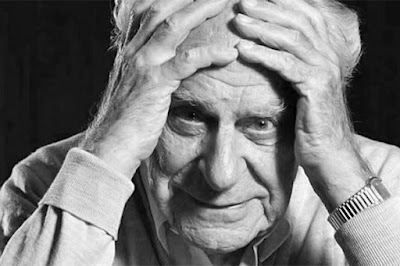

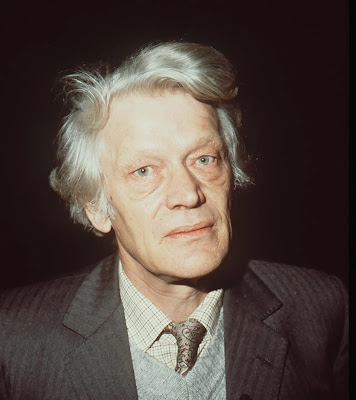

Derek Parfit hit the philosophy firmament in the early 1960s, while Karl Popper arrived on the Vienna scene three decades earlier. David Edmonds' biography of Parfit provides a careful and detailed account of Parfit's main philosophical preoccupations and some details about his life in Parfit: A Philosopher and His Mission to Save Morality. Popper's autobiographical essay in Paul Arthur Schilpp, The Philosophy of Karl Popper Part I and Part II (published separately as An Unended Quest) offers a deeply reflective account by Popper of the evolution of his philosophical thinking. It is very interesting to read the two books side by side, in order to consider two styles of thinking and imagination in the doing of philosophy. Both were analytical philosophers, but their intellectual frameworks and their philosophical approaches were markedly different. Both thinkers are well known in analytic philosophy, and each has energetic admirers and a handful of critics. On balance, I find that I greatly prefer Popper to Parfit.

I read Parfit's Reasons and Persons within a year or so of its publication in 1984, and I never shared the astoundingly flattering assessment of Parfit's brilliance and impact that Edmonds offers. Edmonds closes his book by suggesting that Parfit ranks with Kant and Sidgwick as the greatest moral philosophers of the past three centuries. And he suggests that Parfit's work may have greater longterm impact than Rawls's Theory of Justice. This suggests something bordering on "Oxford hero worship" rather than sober philosophical assessment. And in fact the biography has some of the flavor of "inside baseball" in the world of the Oxford common room, the fellowships, the dons, and the rivalries that defined the context for much of Parfit's career. (Edmonds himself holds a PhD in philosophy, and is certainly well qualified to offer his own assessments of various philosophers. On the other hand, he makes it clear that he has had fairly close personal connections with Parfit over the past thirty years.)

For myself, I have generally found Parfit's philosophical ideas as being annoyingly dependent on clever thought experiments, rather than substantive and sustained analysis of serious issues and principles that matter. (Ironically, the title that Parfit chose for his final work -- and what he believed would be his most important book -- is On What Matters (in three volumes).) The title is ironic because so few of Parfit's chains of argument actually do seem to matter much in the world. To give one example, pertaining to the question of personal identity: what are we to make of a breakdown in the Star Trek teleportation system, where Derek winds up in both the destination cubicle and the source cubicle? Which is which? If Derek committed a crime before entering the booth, which "person" deserves to be punished? (Edmonds makes it clear in another place that the question is doubly difficult, because Parfit doesn't believe that anyone "deserves" punishment for any act; but that's a different point.) Reasons and Persons seems to consist mostly of logical puzzles, conceptual conundrums, and refutations of existing philosophical answers to traditional problems and questions. But in the end, it all seems sort of trivial, and almost a caricature of what good philosophy should be. It has a kind of obsessive character that prevents Parfit from moving forward. (How could a set of Tanner Lectures morph into a three-volume set of books?)

Edmonds refers to quite a few philosophers who became close colleagues and sometimes friends with Parfit. Among them include thinkers whom I would certainly rank as being more insightful and more important to the progress of philosophy on issues that matter than Parfit: for example, Tom Nagel, Tim Scanlon, John Rawls, Bernard Williams, and especially Amartya Sen.

Edmonds closes the biography with some commentary on Parfit's remarkably peculiar lack of interpersonal skills -- no small talk, no special loyalty to the romantic partners in his life, no understanding of the ways in which most people conduct their relationships with colleagues, lovers, friends, and random strangers. Edmonds explores the question of a possible diagnosis of autism in the case of Derek Parfit. This seems like a very reasonable question to ask about Parfit's social ineptitude, but perhaps it is relevant to the obsessiveness of his philosophical preoccupations as well.

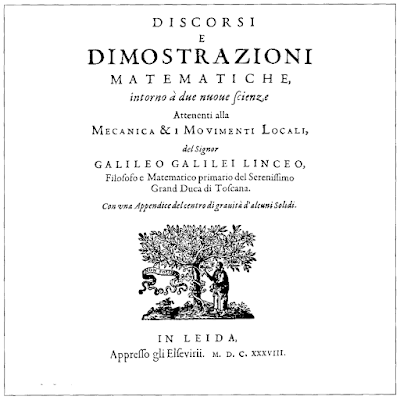

So what about Popper's account of his intellectual development since his beginnings as a cabinet-maker's apprentice in Vienna? Popper's autobiography An Unended Quest is simply fascinating, and it sheds important light on the circumstances, questions, and influences through which Popper's philosophical ideas took shape. Anyone trained in analytic philosophy knows the outlines of Popper's most famous theories -- falsifiability, the demarcation criterion, his rejection of historicism, his rejection of Vienna Circle positivism, his critique of Marxism. What is deeply interesting to me in reading his autobiography is how much more there is to his intellectual and philosophical life beyond these familiar ideas. He seems to have been very deeply interested in music, the visual arts, the breakthroughs in physics of the 1920s and 1930s, recent thinking about cognitive psychology, and the political events of the 1930s, and he thought deeply about each of these topics. Chapters 11-14 of Unended Quest offer a highly interesting and informed discussion of classical western music, polyphony, and innovation in composition. (Here is Chapter 12 where Popper discusses the invention of polyphony.)

Two important features of Popper's autobiography include --

- a very genuine impression of modesty and generous praise for other thinkers -- in contrast to Parfit's view of his own stature in philosophy as a deserving super-star

- a serious, learned, and deeply reflective philosophical mind.

Unended Quest makes it clear that there is much more to Karl Popper than falsifiability and his critique of historicism. This was a philosopher who thought creatively, seriously, and deeply about a wide range of issues that matter in the world. Further, Popper was a philosopher who believed that he saw important analogies across apparently disparate sets of questions -- for example, the serious analogy that he finds between "learning through trial and error" by children and animals and "dogmatic hypothesis and critical evaluation" in science. If Edmonds proposes ranking Parfit with Kant and Sidgwick, I'll propose ranking Popper with Kant and Poincaré for his contributions to better understanding scientific ideas and cognitive frameworks. In spite of having criticized Popper strongly in The Scientific Marx, I now think it would have been wonderful to have had him as a teacher.